This is part 3 of a 5 part series on food preoccupation. Read Part 1, Max's Journey of Healing and Part 2, Is My Child Obsessed with Food? This is a long post because the fear of fat and the consequences of that worry are harmful, and barrier to supportive feeding...

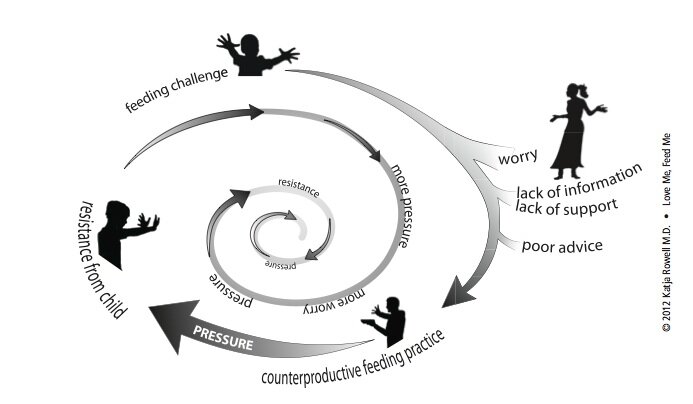

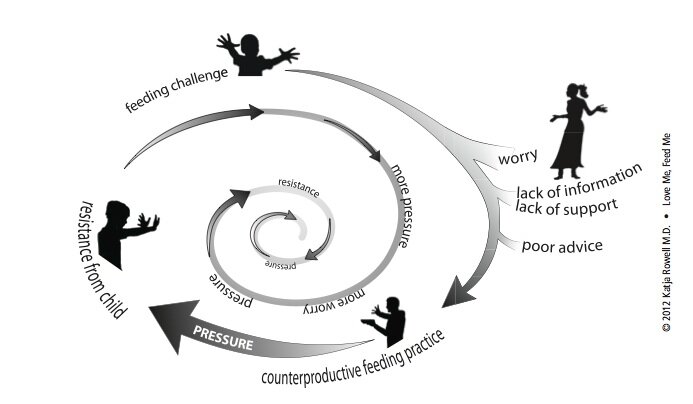

The food preoccupied child is anxious and works hard to get food. The worried parent keeps food from the child. The harder the child works to get food, the harder the parents have to work to keep food away, even resorting to padlocks on the pantry. The worry in this scenario behind the counterproductive feeding is almost universally about weight. The child is perceived as challenging to feed because he is "too big," might get to be too big, or his appetite is "too big" (the worry is still that the big appetite will make the child fat).

Parents receive harmful feeding advice, even from the experts they turn to, who are often unaware of the research and don’t understand that restricting children is harmful and can harm the feeding relationship. Trying to get a child to eat less, or banning "forbidden foods" can lead to a child who is preoccupied, eats more when she has the opportunity, and may weigh more than nature intended. First do no harm.

What Is “Overweight” or “Obese?”

Until we address the fear that drives the restriction, parents will have an almost impossible time trusting the child with eating. As Max's mom shared in Part One, "I don't think I can accept having a fat child... I worry about his health."

When I use “overweight” or “obese” in quotations, I refer to the cutoffs and labels on the standard body mass index (BMI) and growth charts. The child growing above the 85th percentile is considered “overweight,” while the child growing at or above the 90th percentile is labeled as “obese.”

This girl is considered "overweight."

This girl is considered "overweight."

This boy is "obese."

This boy is "obese."

Are these labels meaningful? Consider:

- In other countries, the cutoffs for “normal,” “overweight,” and “obese” differ. Does it make sense that a child at the 90th percentile in America is “obese,” but if he travels to England, that same child is merely “overweight?” They use different cutoffs. This is a clue that these labels are not necessarily clinically meaningful for an individual child.

- A decade or so ago, the child growing at the 90th percentile was considered “at risk” of becoming overweight, and as with adults, the cutoff points and classifications were lowered. Overnight, almost 30 million American adults went to bed “normal” and woke up “overweight,” with no change in actual health.

- In a young child, five pounds can span the label of “normal” to “obese,” and 1/8 of an inch can change the “diagnosis.” While the clinical significance of a few pounds is questionable, the label is not.

Labeling children has not been shown to improve health and is more likely to make your child less healthy. Regardless of actual weight, children labeled “overweight” or “obese” feel worse about themselves, exercise less, and are more prone to practice disordered eating, diet, and gain weight. Parents who are told their child is overweight tend to resort to trying to get the child to eat less, with more dieting and, ultimately, weight gain. “Knowing” is not necessarily a good thing.

Remember that a child growing consistently—even at a high percentile—is larger than the majority of her peers. But to label her as “overweight” when she may be healthy weight for her is wrong, implying a health risk that may not be there. (This article on assessing growth curves explains, "Many children who are otherwise perfectly normal exhibit growth percentiles at the extremes of the growth curves." It's worth a read.) Almost always, the child of the parents I work with is a larger-than-average but healthy child, enjoying good nutrition, with a lot of effort on the part of the parent. Then a worry, either from the parent or from a health care provider who labels the child as “overweight” or “obese,” sets off the cycle of worry, restriction, and food preoccupation, and often accelerated weight gain. Like Max, whose initial growth was perceived to be problematic in Part 1, with higher than average but steady growth, and resulting restriction.

What Children Weigh Now Does Not Reliably Predict Adult Weight

I cringe when families tell me that restriction and outright diets (and diet soda) are recommended for a child of two or three years. As larger-than-average children grow up over the years, they trend toward slimming IF they are supported well with eating and activity. (That is a big IF on purpose.) Child BMI is not reliably predictive of adult BMI. According to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, “a substantial proportion of children under 12 or 13, even with BMIs higher than 95th percentile, will not develop adult obesity.” (Note: There is increasing predictability as BMI increases, and the older the child.)

The youngest age at which I have seen restriction recommended was for four-and- a-half-month-old Mia, an exclusively breastfed baby. The pediatrician told Mom that Mia was “obese,” to cut out nighttime feeds, and to try to hold Mia off her feeding for 30 minutes when she seemed hungry. Within weeks, mom’s milk supply was down to nothing, and this family was on the road to dealing with a child with an increased interest in feeding. In this case, the doctor recommended feeding in a way that was not responsive to Mia's needs (or her moms), which set up their feeding struggles.

“But, can my child be healthy if she’s above average weight?” This is the fear. I hear you. This was my main stumbling block as I was learning.This section will seem to defy every cherished belief about weight and health that our culture and most medical practitioners hold true: The idea that every “extra” pound shortens your lifespan—that weight is linearly related with death and sickness. It is not. There are many healthy people at a variety of weights. Yes, some conditions are correlated (different than causation) with higher weights (mostly adult BMI of 35 or 40 and above), but in studies when fitness level and other disease risk factors were taken into account, the level of fatness did not predict disease. In addition, more research is confirming that health improves (as evidenced by blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol improvements) with healthy behaviors, even without weight loss. You can be fat and fit. If you are reacting strongly to this statement, you are not alone; I remember literally scoffing the first time I heard this. My main point is that if you hear yourself saying, “Yes, but she can’t be healthy and be overweight,” I urge you to read and learn more. If you don’t believe your child can be healthy if she isn’t slim, it will be difficult to trust her and help her become a competent eater. The following books can help start the process: Rethinking Thin by Gina KolataBig Fat Lies: The Truth About Your Weight and Your Health by Glenn Gaesser, PhDHealth at Every Size by Linda Bacon, PhDIntuitive Eating by Tribole RD, and Resch RDYour Child’s Weight: Helping Without Harming by Ellyn Satter, MS, RD, LCSWIt took me two years of reading, challenging my training and my biases to embrace the Health at Every Size (HAES®) Approach.

HAES® is not an excuse to “indulge” children or ignore accelerating weight, as some critics may claim. Feeding a child well and supporting healthful behaviors takes effort and planning. Ellyn Satter's Trust Model and Health at Every Size® simply endorse and support health rather than weight as a goal, and a more stable and healthy weight often results.

When a client says, “Yes, but I don’t want her to struggle with her weight like I did.” I find it helps to ask, “If your child continues to be restricted, food-obsessed, and binging when she gets the chance, what do you see for her future relationship with food and her body?” After some discussion, we usually come to the same conclusion: that the child will struggle with her eating as an adult—and be heavier than nature intended her to be.What are you worried about?

If you would like to join a new private facebook group for parents (moderated to be a safe space), send a “friend” request to Bonnie Appetites (little girl with pony tails) and you will be invited to join the group (and then she will promptly unfriend you). She's not being mean, just protecting privacy.

Read Part 1: Healing a Child’s Food “Obsession”: Max’s StoryRead Part 2: Is My Child "Obsessed with Food?Stay tuned for parts 4 and 5…Parts of this post are excerpted and adapted from my book, Love Me, Feed Me

This girl is considered "overweight."

This girl is considered "overweight."